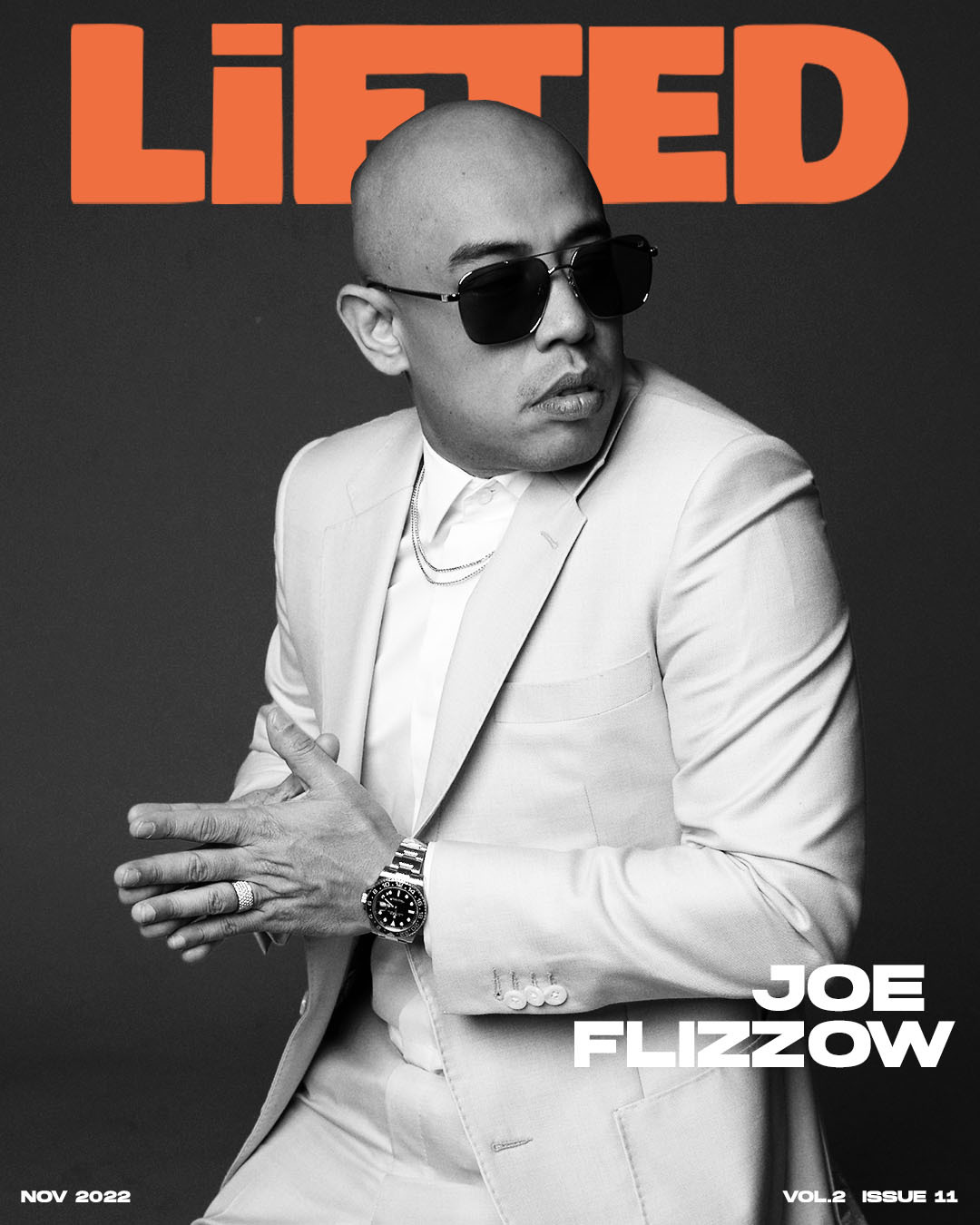

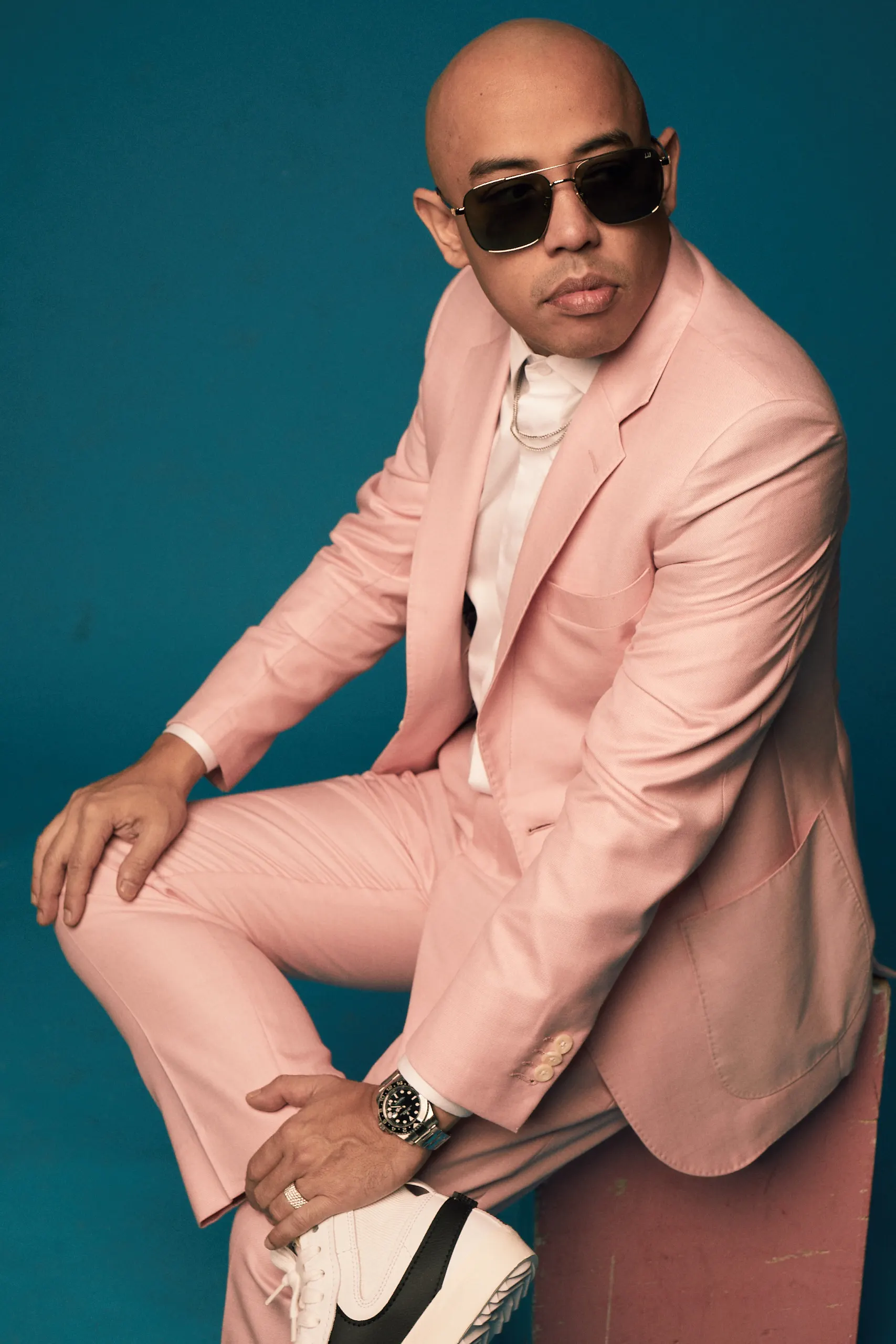

Interview

A Joe Flizzow state of mind

“Our vision is to get that first global superstar out of Southeast Asia”

Joe Flizzow has done it all - underground MC, party promoter, teenage heartthrob, head of an independent label, Malaysian legend, president of Def Jam South East Asia - and is still out here hustling. With a new season of his highly-acclaimed 16 Baris about to drop, LiFTED got in touch with the OG of OGs for an exclusive discussion of his extraordinary life and times in Asian Hip Hop for our November cover.

What were your initial influences and how did you even get involved with Hip Hop from early on as a child?

I think like a lot of people, I think I started obviously as a fan of the music. I come from a very musically-inclined family. My mom sang in a choir. Everybody in the family sings.

With Hip Hop, my uncle had a collection of cassettes and CDs, and he would be the DJ at every family gathering. So I just used to be his assistant. When I was eight, nine, or 10 years old, he said, “Joe, you can handle the music.” I think I just gravitated towards Hip Hop, like L.L. Cool J and all these early Hip Hop albums. I was first attracted to the album covers and fashion, but when I started listening to these rappers, they were talking about different subject matter as opposed to pop singers. That’s what caught my attention early on.

When you were first listening to Hip Hop, could you understand the slang?

I tried to understand it and slowly I started to learn. I started memorizing tracks. I started rapping. Also, earlier when I was a kid, I listened to a lot of Fresh Prince and Jazzy Jeff. They had humorous tracks like ‘I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson.” I was also discovering artists like Ice T Original Gangster or with Body Count. Tone Loc. Anything my uncle had in his collection. I became a student of Hip Hop when I started discovering MCs like 2pac and Nas. That’s when I was 12 or 13 years old and started to get into it.

Was that around the time you started thinking of this as an actual thing you wanted to pursue?

No, that wasn’t until I was 17 years old. That was when I thought this might be something I want to do for real.

Can you tell us about the origins of Too Phat and how that came together?

I had already started rapping a lot in school. I was doing a lot of talent shows. I was just a solo artist, you know? I wouldn't even call myself an artist. I was just like a kid that was like performing covers at a lot of these shows.

I met Malique on IRC. My friends and I were running IRC channel SS15 as that was the name of the area we grew up in. I had a friend who was studying engineering. So he called me and said everyone in his class was doing Rock. He liked Hip Hop so he asked if I would be interested in coming to a studio and recording some raps. When we went to the studio for the first time and recorded a demo, it was actually my boy’s first semester assignment. I copied it to five different cassettes and they would get redubbed. Eventually, we got some sort of buzz and that’s how it all started really.

Soon a promoter heard our demo and asked us to play a live show. We didn’t have a name so he said I’ll call you back in 20 minutes and you give me a name. Where we always hung out was by a skate shop and when kids landed tricks they would say, “That’s phat.” So, looking back, Too Phat might sound a bit corny, but it made sense at that time.

What was going on in Malaysia for Hip Hop at that time? Did the scene even exist?

I wouldn’t say there was a scene. There were pockets of Hip Hop. I would say if you studied the history of Hip Hop in Malaysia, it probably started with breakers and DJs in the 1980s, but when you say scene, I don’t really think that was a scene. It wasn’t united.

What we started in the late-1990s was organizing our gigs. I would say this was the second wave of Hip Hop in Malaysia. We had the advantage of the internet in 97 or 97. IRC chat groups were based on interests. So this channel we created started with 50 or 60 people and became hundreds of people who were fans or bedroom DJs. So this way we had some sort of line of communication instead of just giving out flyers. That kind of snowballed into a movement. We started with 200 people at a show and then it snowballed to 500 or 800. Then two, three, or four thousand people in big auditoriums.

Do you think creating the IRC chat group and putting on your shows was the genesis of your entrepreneurial side?

No, it wouldn’t be until much later when that business side kicked in. Honestly, I was 18 or 19 years old and we just wanted to get an album out. I borrowed money from my mother. I was like, “Don’t send me overseas to study. Give me the money to cut an album.” Every week, we would just save up and record.

Halfway through the production of the first album, we ran out of money. There was a high-flying producer there called Haze, who already was the first Malaysian to have a number one on the UK dance charts. He's like my big brother. And he asked how come we weren’t coming around anymore and I told him we ran out of money. He said we could take the red eye meaning whenever he was done, we could have the studio from midnight to six in the morning. The graveyard shift. And he said once you guys are getting paid, you can pay me back. Until then, we were free to use the studio. That was a real boost that helped us finish this album.

Before this, we went to every label and they told us that since we were rapping in English, we were going to fail. Some labels had a plan for us to start rapping in Malay. We knew we would get there, but there wasn’t any dope Malay rap yet.

How long was it from putting out your first album to starting your label Kartel Records?

We signed a three-plus-one deal, so we did three albums under EMI. When it was time to sign the plus one extension, by that time we were already five years in, and I’m looking at the pros and cons of being an artist. We were dealing with a major label and it wasn’t what we signed up for. Everybody had left. I saw how labels treated artists that weren’t selling as much and it was just business to them. No love. So I asked Malique if we could partner with the label for the fourth record but he was happy to just be an artist. I put up the bread dolo and that was that.

So how did Kartel Records start?

Kartel was just something cool I said ad-libbing at the beginning of a song. Then I realized there were cartels in South America with their product, coffee cartels, and microchip cartels. Cartels were just controlling their prices, so that’s how it came about. We’re controlling our own price. We’re controlling the price of Rap.

We had executive produced all three records, but the fourth was a double CD with 30 songs on it. I realized I’m really handling the production on the album. I’m talking to mastering engineers. I’m talking to artist managers. I liked having the control and putting together my own squads. At EMI, we were just one of many artists that they had.

When our deal was over, Too Phat was over and EMI wanted to sign me as a solo artist. I told them I wanted them to pay for a Snoop feature. The boss said that it was too much money. I told them I’ve made millions for you but he still said no.

It’s funny how things come full circle. Snoop just invited me to be on his global release of Algorithm on a track with Redman and Method Man.

So what happened after Too Phat was over?

So when the group ended, I'm kind of like a solo artist without any tracks of my own. I was just kind of floating in and trying to find my space. And then I got invited to perform at Pattaya Music Festival, and when I got there, it was the first time I had seen Hip Hop in Thailand. I met Titanium and saw them perform in front of 30,000 people. They were rapping in Thai and English and I thought this shit was crazy. Now, those guys are like family and I’ve been to all of their weddings. I kept going back to Thailand and I met Zeebra, NIGO, and the Teriyaki Boyz. Japan and Thailand had that bridge because Thailand was popular with Japanese Hip Hop artists. They go there for vacations.

After meeting Thaitanium, I realized I didn’t need to make it in America. I need validation by my own people, and one way of doing that is to compete with the A-list artists, really build up Hip Hop with a solid foundation, empower other artists, and turn the scene into one ecosystem. But I wasn’t trying to become the next Russel Simmons. No, it was a matter of survival. I was just coming out of a teenage group. I was a teenage sensation, you know. Now, I’m a grown-ass man. It ain’t cute no more. It’s real life.

My former roommate and partner Malique went into Malay Rap and I was like OK, but there wasn’t a competition. I started managing DJs and soon we had the best Tuesday to Sunday Hip Hop nights all over. Then I started going to New York and booking some Hot 97 DJs. We soon signed our first artist and put out a compilation album and started putting out music real proper. At this point David D, who is now the vice president of Def Jam and my business partner, had quit practicing law to join me. He said I could concentrate on the partying and bullshit, but we had someone in the office going over contracts, new business development, that type of thing. He really helped out.

How did you transition from Kartel to Def Jam?

We had kind of hit the ceiling with what we could do in Malaysia, as an independent label. We were thinking about a regional label, but that didn’t work out. We were trying to get Universal to hire us as consultants because we got the connects. We knew every rapper in Thailand, every rapper in the Philippines, and every rapper in Vietnam. Because now the network is strong. It’s not the fake-ass industry-type relationship. It’s real-life shit.

By this time, Asian Hip Hop had solidified especially after 2007 when they did the first Asian Hip Hop festival. We had all the big rappers from Taiwan and Indonesia, and we flew in Nas. So that was the co-sign. The whole movement was crazy.

We heard Def Jam was coming to Asia and we were on their radar. I soon read all of Russel Simmons’ books and Rick Ruben’s books. So I was well-versed in how this label started. I did a short course at Harvard in 2016, and my classmate was L.L. Cool J. Just talking to him gave me more insight into Def Jam. I looked at artists like Jay-Z and they had Roc-a-fella, which was kind of like Def Jam. Some people may argue he wasn’t that good of a CEO but he signed Kanye and Rihanna so what else does he have to say?

So we announced Def Jam in 2019 in October and we had four or five artists who were our artists from Kartel and then it just hit. We are back in full force after COVID-19 and have offices in six countries and 30-plus acts. I’m doing a lot of distribution for rappers.

You’ve seen the Golden Age of Hip Hop plus the 90s and 2000s, and now you are seeing rappers who are half singers and entertainers now. What is your vision for the world of Hip Hop and Southeast Asia especially?

Our vision is to get that first global superstar out of Southeast Asia. I feel like it’s something that’s achievable. You know how it was inevitable that the first Asian was going to play in the NBA? I feel like this guy's going to be the same way in Hip Hop. Whether this artist is going to come out of the Philippines or Indonesia remains to be seen. But our long-term goal is to really deliver a global superstar.

Short term, we want to empower people. Def Jam in Vietnam has to be strong again. Def Jam in Asia has to be popping in Malaysia. We have to be a team player in the industry. We’re not coming in like we are Def Jam so move aside. It’s not like that. It’s more like how do we work together? Treat me like a bank. You need money? I can give you that advance you need for you to grow your label.

I guess we could do more things for smaller acts or other independent labels, cause I was there before. So I will always come from that angle. I will never be Mr. Major Label because I understand your problems and the difficulties that smaller labels have. How can we help you? This mentality is important to have in every Def Jam office. To be seen as a player in the industry, we need to do grass-roots events. As much as people want to do 20,000-person festivals, you still need to do the 500 or 600-person venue.

Another short-term goal is to have crossover artists. Southeast Asia, despite having 660 million people, is divided not just by country but by language.