Scene Report

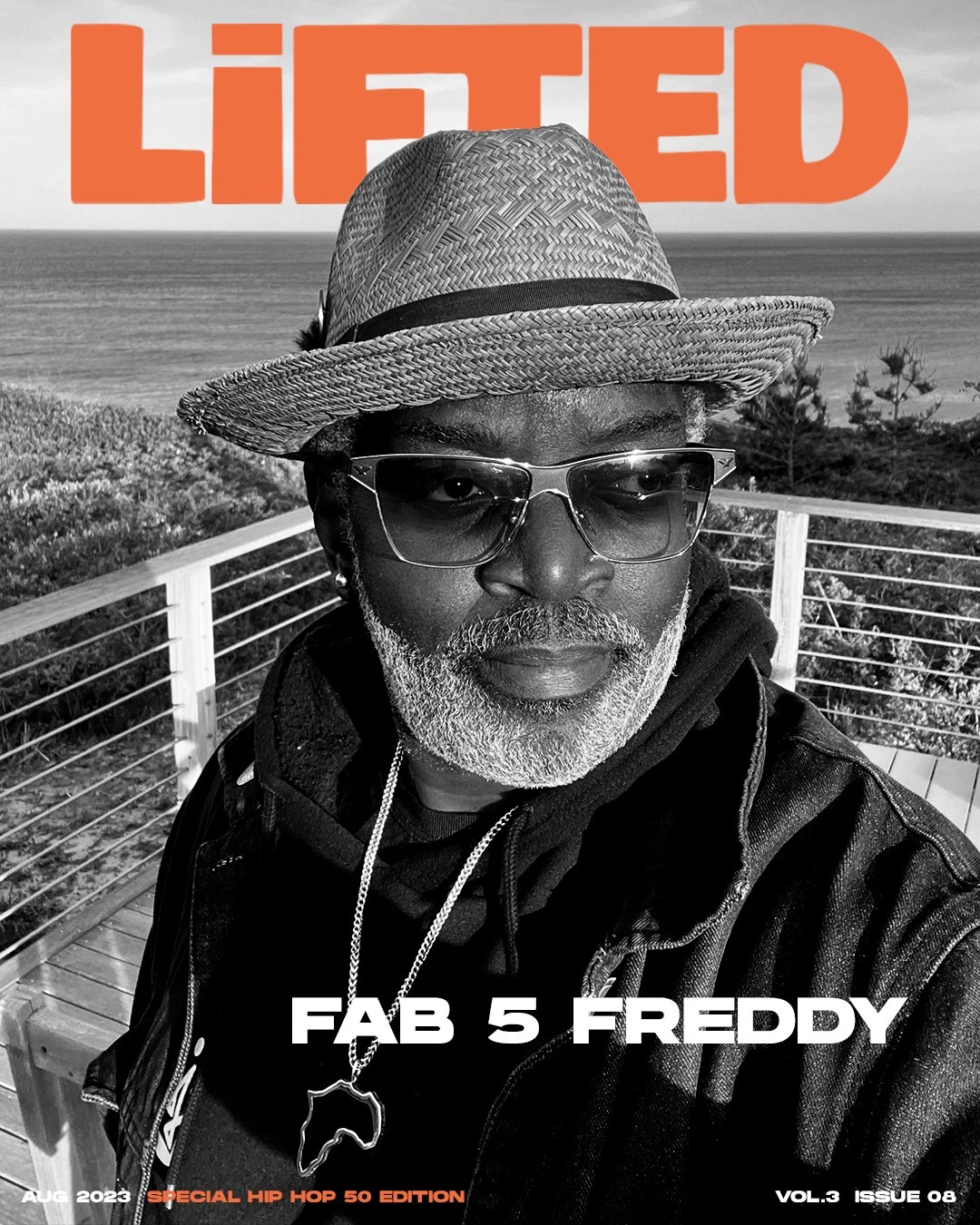

The legendary Fab 5 Freddy breaks down his journey in Hip Hop

A special Hip Hip 50th anniversary edition cover

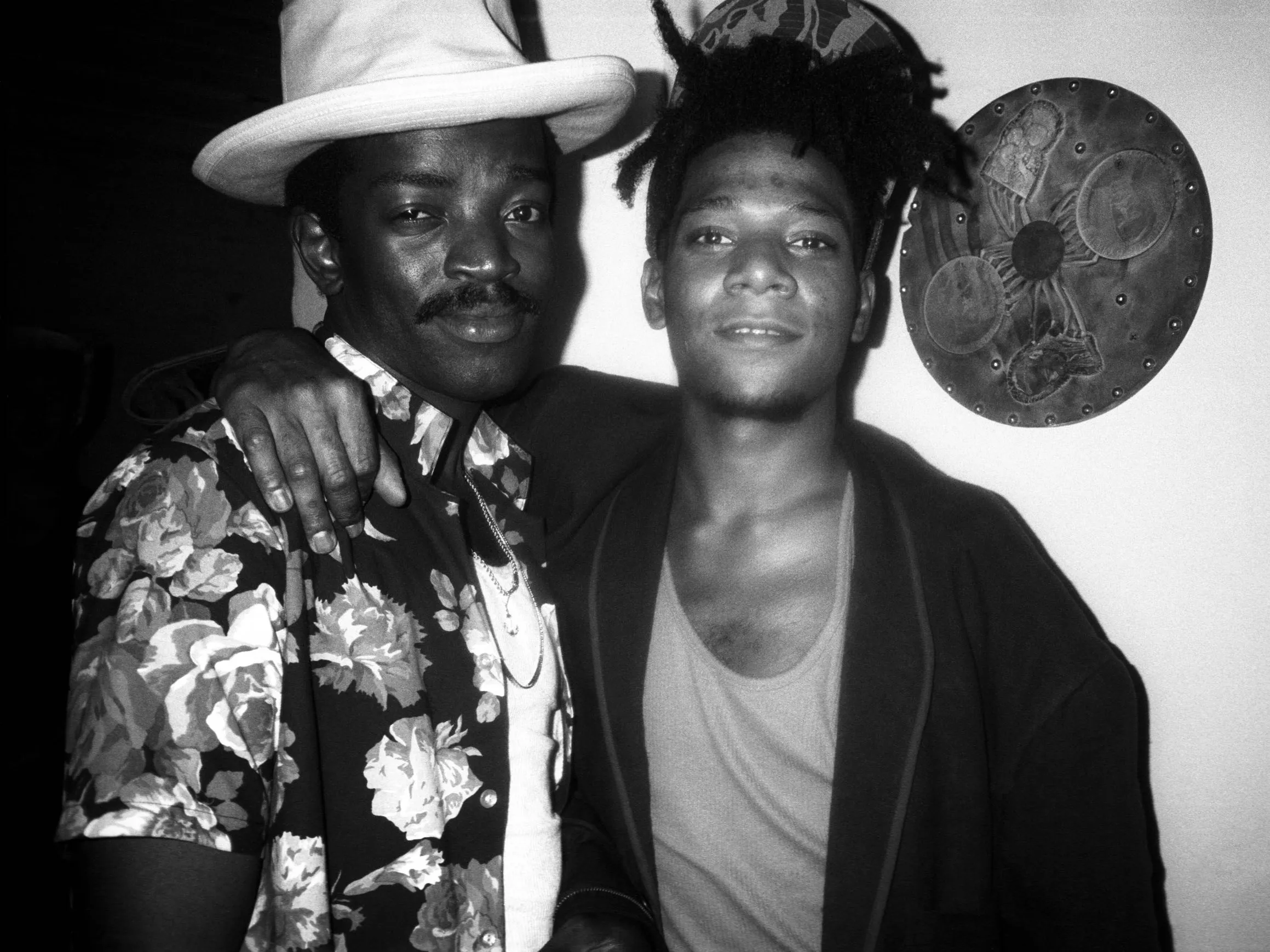

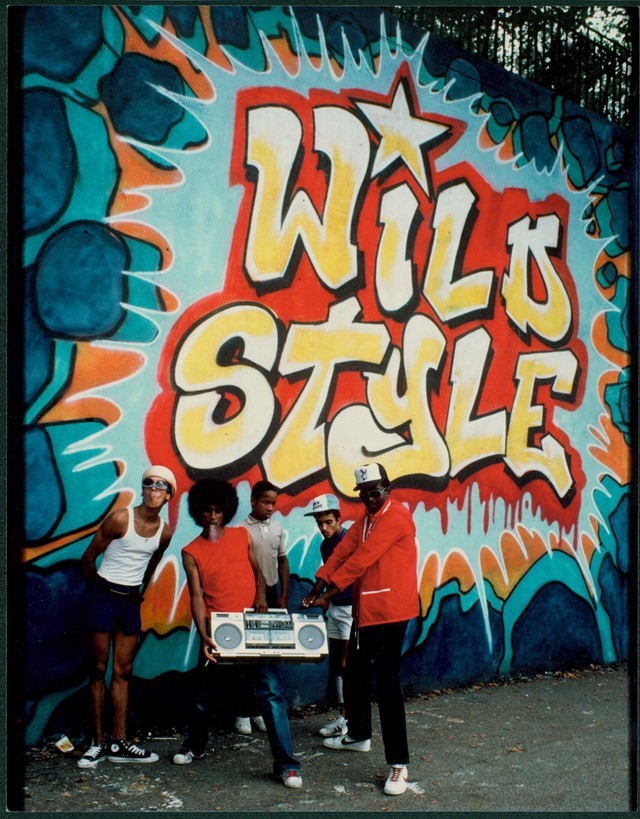

As Hip Hop turns 50 years old this year, LiFTED wanted to take time to salute the culture, and give props to the originators who created the music, dance, art, and style that has spread out into every corner of the world – especially in Asia! Who better to talk to than one of the original architects of the culture, Fab 5 Freddy? Starting in the early 80s, Fab [and his partner in crime Jean Michel Basquiat, RIP] was instrumental in bringing the then-fringe Graffiti Art movement from the subway cars and outer boroughs of New York to the bubbling Downtown art and club scenes. Fab 5 Freddy saw the vision of what the nascent Hip Hop culture truly was – Graffiti, Turntablism, Breakdancing, and Rapping – and together with another visionary, director Charlie Ahearn, created the first Hip Hop movie, Wild Style, in 1982.

To say Wild Style put Hip Hop on the map is just facts. For most Americans – even New Yorkers - it was the first real look at what was cooking in The Bronx, and throughout the other boroughs wherever Black culture thrived. Before the decade was over Fab was at it again, helping create and hosting MTV’s first-ever Hip Hop show, Yo! MTV Raps. During that historic run, in the Golden Age of Hip Hop Freddy went on to direct more than 75 music videos for some of the biggest names in the game, like KRS One, Snoop Dogg, Nas, Gang Starr, and others.

In the 21st century, Freddy has continued to be one of the most important voices in the culture, while maintaining a position of importance in the contemporary Street Art world, with gallery shows in NYC, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, and the Smithsonian in Washington DC. He is currently showing at the massive Beyond the Streets exhibit in Shanghai. It’s with great pleasure that we get to sit down and break it down with Hip Hop’s true renaissance man, Fab 5 Freddy.

Yo Fab! What’s good? Thanks for being part of our coverage of Hip Hop’s 50th anniversary.

Yo! It’s a great pleasure to do something with you again. The great publication and information Hip Hop source L.i.F.T.E.D.!

Let’s take it all the way back, to 1973 when Kool Herc first did his thing in the Bronx, before Hip Hop even had a name. What were you doing back then in 1973?

Well, you know I’m from Bed Stuy, Brooklyn and I was a young’un at that time. I probably wasn’t aware of Kool Herc, or even know much about the Bronx at that time, but I was following local mobile DJs who were known then as Disco DJs who were doing this way before the Disco movement blew up with Studio 54, Saturday Night Fever, John Travolta and the Bee Gees. All of that started with Black and Latin mobile DJs who were playing the hot Dance, Funk, and Soul records of the day. The term Disco caught on – derived from Discothèque in the 60s – and then it just blew up.

So that’s what was going on with me in ’73 hanging out in the streets of Brooklyn. Maybe tagging the walls a bit back then, too, but at that time Graffiti hadn’t evolved into what it became. That got started by dudes like TAKI 183, who was a Greek kid from Washington Heights who had a messenger job that took him all over New York City, and he kept his marker on him and wrote his name everywhere he went. Back then, it was just your name and the crew you hung out with, or if you were from Uptown, your street number. So those examples are the beginning elements of what would later become known as Hip Hop.

For a lot of Downtown New Yorkers, Rap music and Graffiti first got big in clubs like Danceteria and Mudd Club, also in the East Village at places like the Fun Gallery. You played a big part in making that happen. What was driving you to expose this new art to the rest of the established art world?

What was driving me at that time - basically I was planning an assault onto the emerging creative scene Downtown in New York. I wanted to inject myself, as a visual artist, into the scene. I was learning about people like Andy Warhol and Pop Art. I read a lot of art books and became fascinated by the Pop Art movement. I started to realize that the same things that were attractive to those artists in the ‘60s were what Graffiti writers were inspired by - big, bold beautiful letters, colorful brand logos, comics, etc. Some writers had started doing trains by this time, and that became their biggest canvas. Also, I noticed that these cool visual artists and musicians were also hanging out in these hip new clubs Downtown, and it looked like a lot of fun and I wanted in on that. I also started getting interested in the Punk and New Wave scene by finding and reading fanzines and I felt like these artists were open-minded people, and what they were doing was similar to the emerging Rap scene. The music sounded different, but it had the same rebellious spirit. So, I thought if I could go across the bridge from Brooklyn to Manhattan and get into this Downtown scene, I could try to connect these ideas in my head about art and music with some other like-minded souls.

This led to me meeting people like the brilliant Glen O’Brien, who was part of Interview magazine and therefore Andy Warhol. He in turn introduced me to Chris Stein and Debbie Harry from Blondie. Also, at this time I started to hang with Jean-Michel [Basquiat] a lot and we became good friends, as he had a similar desire to be an artist and break into this new scene.

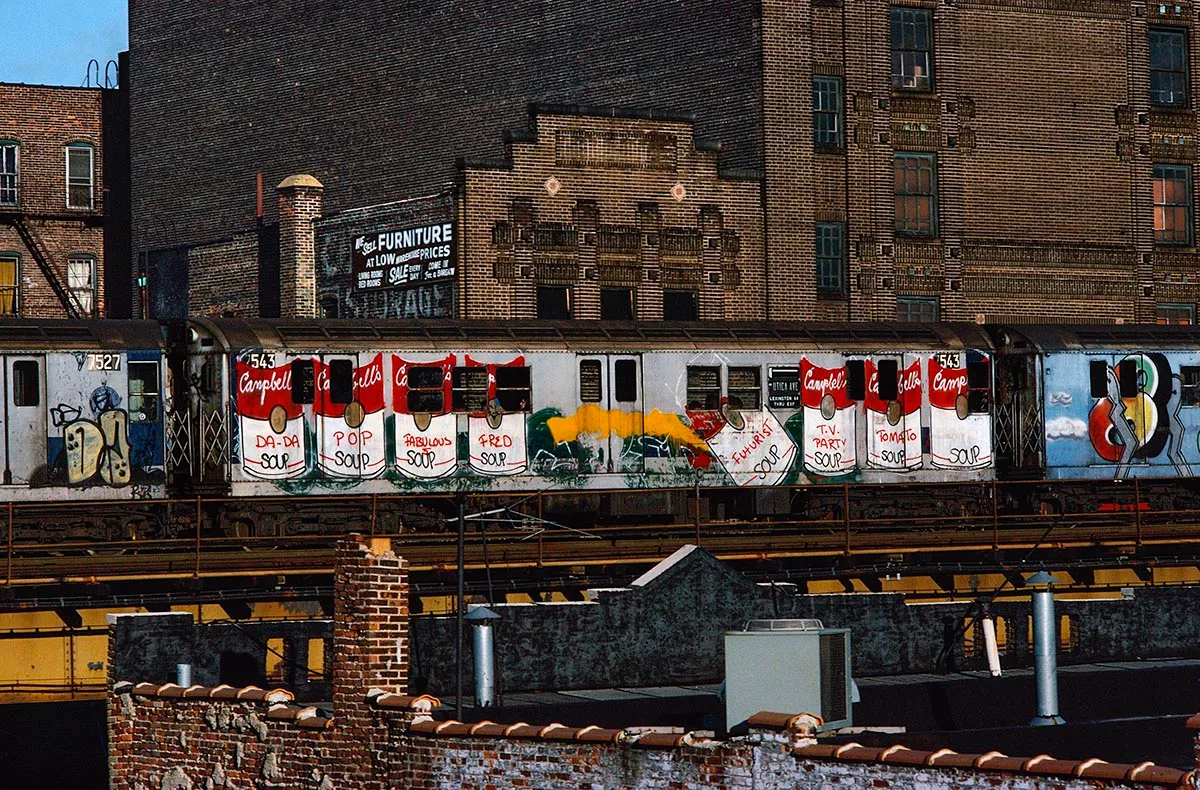

Your Campbell’s Soup cans full car burner is one of the most iconic graffiti train pieces of all time. What made you want to do an homage to Andy Warhol on a subway car?

So, like I said I had become sort of an art super nerd, and I was studying Pop artists like Warhol, Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenberg, and others. But Andy was the one who impressed me the most, he just had this whole sly persona, and what he did with everyday American logos like Campbell’s soup was just incredible – how he had turned them into high art. So, like I said, I wanted to connect what was happening in the Uptown Rap scene and on the trains, with what was happening Downtown in the clubs and alternative galleries. I figured if I could paint a tribute to Andy Warhol’s art on a subway train, then maybe some people in the art world would notice that some of us were serious about being artists and that we were aware of the history. Also, I wanted to give an example to other writers that we could have more interesting subject matter than just painting our names in elaborate, colorful ways. And right now, at the massive Beyond the Streets exhibition in Shanghai, I did a life-sized re-creation of that subway piece on multiple canvases.

The period between 1980 and 1984 was so fertile for Hip Hop. First you and Charlie Ahearn came out with Wild Style in ‘82, documenting the culture as it really was. By ’84 RUN DMC came out with ‘It’s Like That’ and ‘Sucker MCs’ and the whole sound and look pivoted. What was that period like for you?

Wow, well once I was involved with the Downtown scene with a few other people like Jean Michel, I started to bring some others like FUTURA and ZEPHYR around – because there were so many Graffiti writers who were making great art and that scene was really expanding. And I had this idea to make a film that would document what was happening, but also because at that time depictions of Black and Latino kids in the news were almost always negative. I wanted to change that perception and show that we were also creative. I wanted to show that Graffiti, DJing, Breaking, and Rapping were all part of the same culture. At that time, all these scenes were happening kind of independently of each other, but were all connected and starting to blow up separately. There was no concept of Hip Hop culture yet.

I met Charlie Ahearn at an Art opening for the Times Square show in 1980, and when I found out he was a filmmaker I pitched him the idea to make this movie that would become Wild Style. He was already aware of Lee Quinones, and had seen his art. We decided to make a low-budget, gritty film about the real scene, using the real artists as actors. So, all the actors in Wild Style are really the ones who were creating the scene at that time. Lee was probably the top Graffiti artist in NYC at that time, so he played the lead character. The Cold Crush Brothers and Grandmaster Flash were laying the foundation for what would become known as Hip Hop, Rocksteady Crew was the top B-Boy outfit at the time, and the Graffiti writers in the movie were all the ones who were up on the trains.

When Wild Style came out, it had a much bigger impact than we ever dreamed it would. We showed what the city looked like then, and parts of Harlem, the Bronx, and the Lower East Side looked like bombed-out war zones. All that realism just connected with a lot of people. By ‘84 music was also changing, and early groups like Run DMC, Whodini, LL Cool J, and others started to get in the studio and make records that reflected this same energy from the New York streets. The sound was evolving quickly because the competition was so strong, and a new generation of rappers was emerging. There were no rules at all, just creating something from next to nothing.

The period between 1984 and 1994 in Hip Hop is probably the most prolific spurt of creativity and innovation ever within a musical genre. It felt like every month a new rapper with a new sound would come out who was nothing like the previous ones. From Run DMC to Public Enemy to Biz Markie to De La Soul and then the beginning of the West Coast sound with NWA…it was just incredible. And you were there hosting Yo! MTV Raps and directing so many of their videos. What was it like at Yo!?

Man, yeah that was just an incredible explosion of creativity. You could say from the mid-80s to the mid-90s is the so-called Golden Era and Hip Hop was getting so big that records were coming out and going gold with almost no marketing behind them – just word of mouth and the streets letting you know from boomboxes. I met a guy called Peter Dougherty who was getting started at MTV. He wanted to do a show about Hip Hop but at that time MTV was so white, and there were almost no people of color on the show except maybe a Lionel Ritchie or Michael Jackson video here and there. But this segregation really reflected a lot of what radio was doing, too. We started Yo! MTV Raps in the fall of ’88 and immediately it became the most popular show on MTV. I was the original host, and when they decided to make it a daily show they brought in Ed Lover and Dr. Dre, and I did the weekends, flying all over to interview new rappers and new music that was starting to come out all over the country. I got to interview a lot of artists for their first time on television, like NWA in Los Angeles, the Geto Boys in Houston, and Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince in Philly – it was a great time. Looking back, it was also an incredibly humbling time because I was able to be part of so many incredible stars’ first time on national television.

When MC Jin dropped ‘Learn Chinese’ after kicking much ass on the BET 106 & Park Freestyle Fridays show, it was the first time an Asian rapper really made noise. Now Hip Hop is the fastest-growing music genre across Asia. You’ve spent time in Asia and traveled the world, did you ever think Hip Hop would get this big? How does it make you feel?

I went to Shanghai in 2009 and then to Hong Kong in 2012 – where I did the KUNG FU WILD STYLE Art show with MC Yan – and that really opened my eyes to a lot of stuff. Especially the lasting impact of Wild Style in China and around Asia. I remember when Jin was tearing it up on those freestyle battles on BET, and he was winning every week and people started talking and then he got a record deal. It kinda reminds me of Linsanity when Jeremy Lin went on a tear with the New York Knicks and became the toast of the town. No Chinese player had ever captured the imagination of the country and even the world like that before. So, when Jin did his thing the whole community got behind him because he was nice!

That’s the incredible thing about Hip Hop, it’s Black music but it’s always been embracing if you can do your thing. If you can put those words together over the right beat in the right way, you’ll get love. And Jin definitely experienced that love. It just makes me feel so humbled and delighted that this thing that we started so long ago has become so big and touched so many people all around the world. It’s amazing, and I can’t wait to get back over there so I can see some of the artists I see you guys writing about in LiFTED!

We’d like to ask you a question about the Four Pillars of Hip Hop. Who’s your favorite rapper? Favorite DJ? Favorite Graffiti artist? Favorite B-boy?

I can’t answer these questions, simply because there are so many! I mean, which era? I’ve been involved with Rap music since Grandmaster Caz and Melle Mel to Run DMC and Big Daddy Kane and Rakim. It’s just too hard to pick only one. You know, there are artists who made just one great song, but every time I hear that song it hits me the same as another guy who might have made five albums. So I can’t pick. Sorry!

We loved the Netflix documentary you directed The Grass is Greener. Do you have more projects like this coming out? What’s the near future looking like for you?

Yeah, you know cannabis has been my main get down for a long time. Whether it’s for medicinal purposes or recreational, cannabis has never killed anyone, ever. So, I wanted to make a film about the history of cannabis in America, especially in relation to music – from Jazz all the way up to Hip Hop. You know, in almost every era of every genre of music history, cannabis has been a big part of the artists’ stories. It’s a drug that can help you expand your creativity, so it’s natural that artists would use it. From Miles Davis to Charlie Parker to all the Rock stars and now to today’s Hip Hop stars, cannabis has always been big. So, in my film The Grass is Greener, I wanted to document that, and how US laws have always classed the drug next to dangerous drugs like heroin, which makes no sense. And further, how Black and Brown people have always been demonized and jailed disproportionately for using it. There are still many people in US prisons, mostly minorities, for non-violent cannabis use and I wanted to shine a light on that.

I created a cannabis brand called B Noble after a Black man Bernard Noble who was jailed for 13 years for carrying a tiny amount of cannabis, and 10 percent of all sales go to various foundations that help people in his position with legal support and help to get their lives back on track. Hopefully it will become legalized in the entire country and can be used as a medicinal plant as it always was, even in ancient India and China.

Word, thank you so much for taking the time and for dropping these historical pearls on us.

Thank you for having me!