Scene Report

Singapore’s Breaking scene weighs in on the Paris 2024 Olympics

A brief look into the history of Breaking, the Singaporean scene & what the Olympics stage means

When Breaking was first announced to debut as a sport at the Paris 2024 Summer Olympics game, the Singaporean scene was split. It’s safe to say it wasn’t an overwhelming celebration like the Olympic chiefs might have expected. On one hand, the Olympics provides a global platform for Breaking, but on the other hand, categorizing it as a sports competition alludes to the idea that the athletic aspect takes precedence over the artistic expression of the dancer, as well as the culture that surrounds Hip Hop and Breaking – when the two are intertwined and paired like conjoined twins.

To understand Breaking as an art form, one must first understand its culture. Breaking is one of the pillars of Hip Hop, alongside MC-ing, DJ-ing, and graffiti. It began in the 1970s in The Bronx, New York, as a form of self-expression, representing the youth's response to the social, economic, and political climate back then.

It started with the music first. DJ Kool Herc, widely regarded as the Father of Hip Hop, saw people dancing to breakbeats at block parties, which led to him isolating beats to create longer breaks for dancers. The sound of Breaking emerged from a specific canon of fast-tempo beats in Hip Hop music, inspired by African American, Caribbean, and Latino sounds. The art form became an integral part of these lively block parties, taking inspiration from different dance styles. It started with cyphers — a space on the floor surrounded by a circle of onlookers. In this space surrounded by spectators, Breakers would take turns dancing. Then, it became almost something of a staple at parties. The iconic Breaking sound we know today was born from the DJs’ musical innovations, prolonging breaks to extend the Breakers’ performance time. Breaking has a rich vocabulary, but the five main styles of movement are Top Rocks, Go Downs, Footwork, Power Moves, and Freezes.

Top Rocks refer to dancing while still standing, before going to the floor. Some examples are the Cross Step or the Indian Step. Breakers usually do a combination of those steps with hand and arm gesticulations, playing with the rhythms of the song to showcase their style and musicality.

Go Downs are the transitional moves Breakers use to go to the floor from standing, such as Knee Drops and Corkscrews. Footwork, on the other hand, refers to when a Breaker is on the floor, using their hands for support while moving their feet in a series of steps. Common examples would be a 6-step, a 3-step, and Shuffling.

Freezes are essentially as described: when a Breaker hits a pose on their hands and holds that fixed solid shape for a couple of seconds. Usually, this is done to reflect a prominent note in the music or used as a full stop to end a set of movements. Examples include the Chair Freeze and the Shoulder Freeze.

Power Moves are the star of the show — they add a dynamic element to the dance, usually involving a Breaker spinning their entire body while balancing on their head, shoulders, back, hands, or elbows. These usually end in a freeze, continue to a different power move, or transition into a series of Footwork.

Many also use Tricks and Flips to add an unconventional and dynamic element to their movements.

As if Breaking moves weren’t already physically demanding, they are all executed with non-stop flow, in tandem with the music playing. It might seem highly technical at this point, and it is, but the idea of Breaking is all about self-expression and showing who you are. This sense of freedom is what spoke to many back then, and it is why so many around the world resonated so deeply with the art form.

Today, Breaking has evolved into a global phenomenon, just like Hip Hop did. Kids and adults from every corner of the world are living and breathing it, and Singapore is no exception to it.

How does this culture take shape in a country like Singapore? It was first popularized in the 2000s with the likes of MTV and Hollywood films dominating the screens. Singaporeans, like the rest of the world, readily embraced it and all that it came with. For many, the love for Breaking starts through many different touchpoints. Be it the initial thrill, the challenge it offers, the impressive power moves, or the music. However, when asked, Singaporean breakers bring up the notion of the community found.

B-Girl Seana shared, “It's about having like-minded people, those who all love the same dance and we come together to create and hone our craft. Recently, I went to Australia for a Breaking camp, and one of the most memorable things for me was the moment I cyphered with strangers and we shared our craft. It felt like we were already friends just from the connection of the dance. Breaking is a way to communicate and connect with others.”

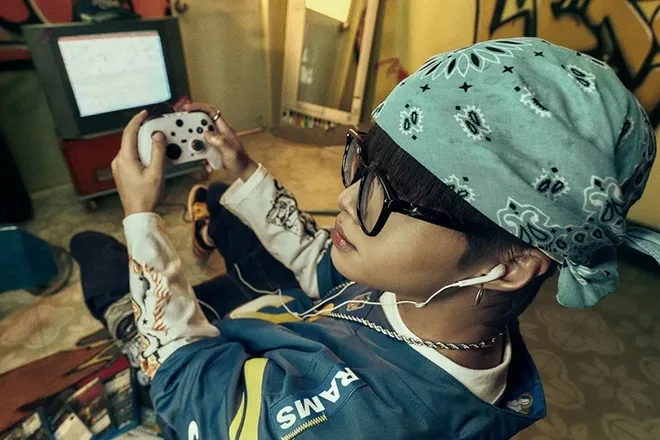

Sean Shagaran, two-time Red Bull BC One Singapore winner

The beauty of Breaking is the ways it foregoes geographical borders and language barriers to facilitate connections. The spirit of exchange is also integral to the Breaking culture, enabling vastly different cultures around the world like Singapore to grab hold of it. It is what permeates the growth of the Singaporean Breaking scene. The scene has grown from having one or two battles and jams annually, to a couple every other month.

For a tree to grow, it first must rely on its roots. To continue growing well, a tree needs consistent tending. Just like trees, a scene can only develop because of the foundations laid by the impassioned pioneers who came before, and those who continue to nurture it. Without their efforts, who's to say what could become of it today?

The Singaporean Breaking scene has many to thank for actively supporting and contributing to it, making it what it is today. Among them is Felix Huang, founder of Recognize! Studios and member of the pioneering breaking crew, Radikal Forze. Huang is also the main organizer of one of Asia’s biggest dance events, Radikal Forze Jam (RF Jam).

Micheal, founder of Elevate The Streets, a community focused on building the Singaporean scene with jams, mentorships, and shows. Shawn Lim (Slim), a DJ and B-Boy who now teaches at Artistate, alongside Jem, Sean Shagaran, and Gerald. Like them, many others in the scene find meaning in elevating and inspiring the next generation to continue Breaking and growing the local culture.

The Singaporean brand of Breaking differs from what you might see in other parts of the world. B-Girl Seana highlighted that a large emphasis is placed on Breaking foundations rather than power moves, which “helps to hone and discover their own unique style.” Not everyone has the same approach, but having a deep understanding of foundational moves develops a better understanding of one’s body, opening up a wider range of creative pathways. “Another thing is that we love threads, and Singaporeans come up with the craziest and freshest threads I've seen,” she continued.

Artistate B-Boy instructor Jeremiah, on the other hand, describes Singapore’s mold of Breaking as a “sponge”. “Most Breakers in Singapore are able to absorb knowledge and apply it at a phenomenal rate”. Yet, this approach is done with a high emphasis on “creativity and individuality”, adds fellow B-Boy instructor Slim.

Now, the scene has become much more commercialized. There’s an emergence of more studio-based learning as the Singaporean scene matures and becomes more organized. Since the idea of Breaking is about self-expression, this development might seem contradictory.

The dichotomy is that a polished, studio environment may restrict the raw and free essence one has, as opposed to a jam or a cypher where everyone is having fun without the emphasis on competition. A less structured setting arguably conceives a more intuitive expression, closer to the original essence of the art form. Hence, some might see this evolution as a dilution of the culture, while others welcome it.

Singaporean Breakers do acknowledge that the commercialization of street dance creates more opportunities for professional Breakers to pursue dance as a full-time career. As B-Girl Liz frankly puts it, “Dancers need to eat.” The prevalence of studios opens up doors for the newer generation to try their hand at Breaking.

B-Girl Liz at the Red Bull BC One Regional Cypher Philippines 2024 Finals

For example, if a Breaker wins at a global stage like the Olympics, it may open up opportunities for brand deals, partnerships, and teaching opportunities locally and overseas. A medal at The Olympics would also add a sense of credibility to the Breaker’s name and ability, potentially paving the way for the dream full-time career.

Likewise, studios are just another place for Breakers to learn, connect, and hone their craft. Ultimately, the win that Breakers will take is the increased exposure of their art. The more important part, however, lies in the sharing outside of commercialization. Whether it’s on the streets or in studios, what matters is keeping its culture alive and passing the history on to the next generation.

Breaking itself has become more competitive as [dance] battle culture grew over the years and the generations that come after are naturally further removed from its genesis. Nowadays, there are fewer jams and more competitions, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s a give and take situation. Battles are a place for Breakers to get their name out there, as much as it is a place to jam and exchange.

There’s no denying Breaking’s high level of athleticism, but it is still an art form. It begins with the music, how does it make you feel? How do you express it? Battles are highly subjective, dependent on not only technique or power moves, but also interpretation of the music, originality, and creativity.

What demarcates Breaking as something fit for the Olympic judging criteria is still up for debate, because it encapsulates a whole plethora of things: creativity, personality, technique, variety, and musicality. If you look at the Olympics as a Breaker, it may just feel like another big-stage battle. There were Breaking battles before, and there will be Breaking battles after. Nonetheless, the Olympic stage is a huge global platform that promotes the art form and its Breakers and a medal that is justifiably vied for.

One B-Boy, who’s been Breaking for four years and represents the Damage Done crew, notes that as an Olympic sport, the raw energy intrinsic to Breaking is amiss. But he stays optimistic about the growth of the scene in today’s times, “My take is that with mainstream media attention, there will be avenues to portray what we want to. Breaking becoming more commercialized has more pros than cons in my opinion. There will be more opportunities for us.”

He continues, “I’m very much for it. As much as breaking is an art form, it’s also very much a sport due to the physical demands on our bodies. Additionally, the publicity we can get from breaking being in the Olympics will allow breaking to be more mainstream, bringing in more people to be interested in it.”

For Breakers and those aspiring to get into Breaking: keep nurturing this vibrant community. Continue honing your craft, pushing boundaries, sharing, and expressing yourself. Perhaps, the next generation will look back after some time and see the lush, thriving landscape they’ve cultivated alongside many others.